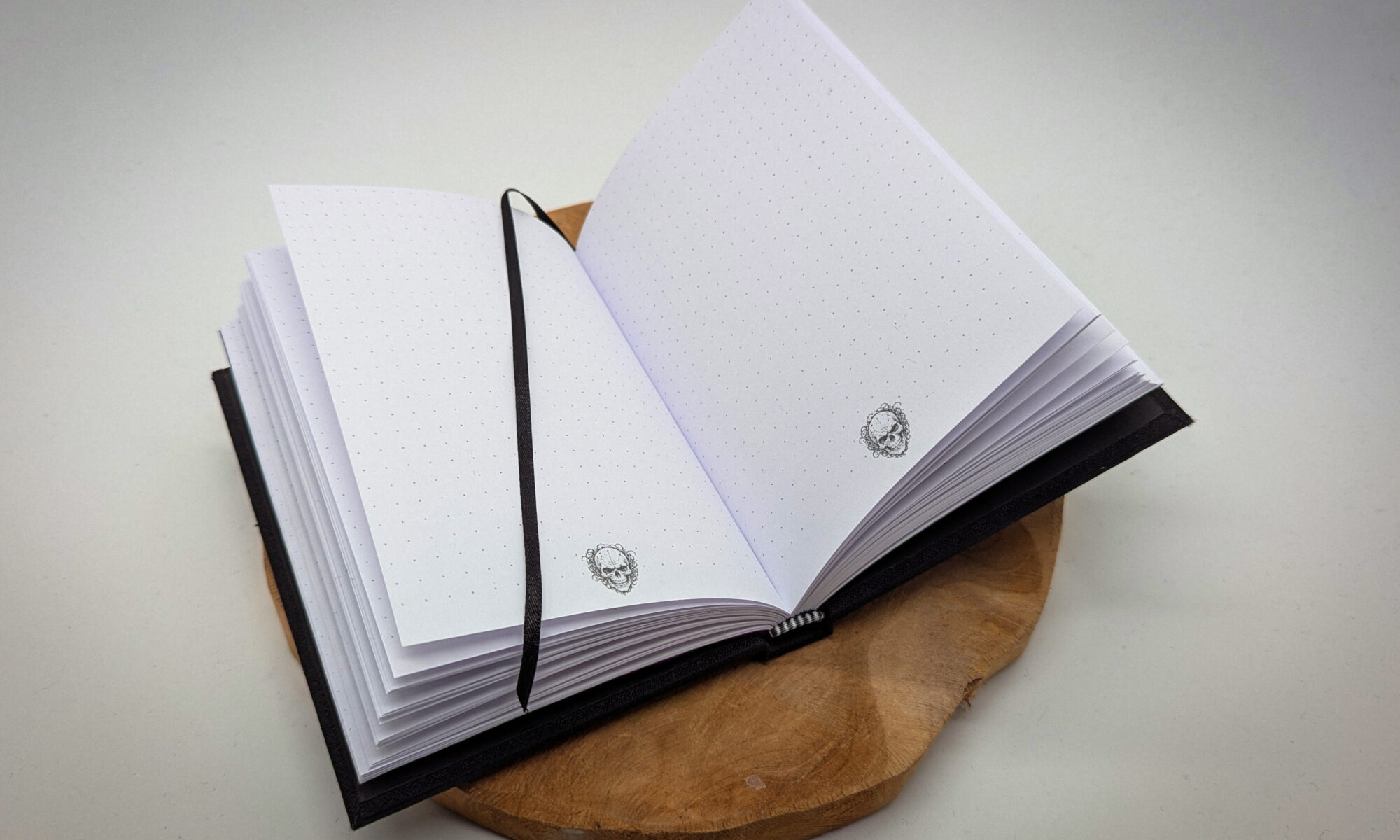

I not only make knives, but I like to try out many different kinds of handcrafting. Learn more about my handmade notebooks and how I make these neat little daily companions for your pocket. Turn them into your own, take notes, write a diary, or turn them into your own daily journal.

Continue reading “Make journaling your new daily habit”EDC: Signature’24

A 2024 remake of my Signature model. It combines the lines of the Tigershark model with the short blade and handiness of an EDC knife. The handle was made out of bog oak and red and white paper micarta liners.

Read my blogpost about making this EDC Signature knife.

Continue reading “EDC: Signature’24”Making a new Signature Model ’24

My Signature knife was the first knife I ever made, and it is still my companion on my journeys and my EDC. But I wanted to take it to the next level and bring in new elements I learned over the years

Continue reading “Making a new Signature Model ’24”A long way, but finally…

It took me a very long time to finish my last two projects. I had another Furutsu and a Spring Folder in my books and struggled to finish them.

Continue reading “A long way, but finally…”The heirloom knife – the Warrior Heart

This project caught me as soon as I understood what the goal was. A father contacted me with the idea to build a custom-designed Bowie knife for the eighteenth birthday of his son. With the idea that it will become a future family heirloom.

Continue reading “The heirloom knife – the Warrior Heart”Pushing my limits with a Kopis knife

With every knife I made I learned one or two new things. With this Kopis build, I aimed for: “let’s try what I can do at max without limits” and trying all the stuff I had on my list for future builds.

I had seen some ancient Kopis swords in pictures and similar to the Kukri III I wanted to make a smaller knife version of it. Again I also decided to give it a modern look. The blade was designed and I pushed myself to even try a hollow grind, freehand on a big recurved blade – yeah, why not try something easier first? It came out a bit uneven and I hoped to compensate for that during hand-sanding. As this knife should become my actual masterpiece I was expecting hours of hand-sanding anyway.

The handle should be also a new technique and I chose to do a frame handle I never did before. As Kopis swords are from ancient greece, I found nice curly olive wood to fit pretty well. As a contrast, the frame should be done out of ebony wood and some veneer liners. The handle itself would consist out of 12 parts that had to fit perfectly to get the final flush results. Everything was sanded on a flat surface to have perfectly flat sides.

I brought the blade to an 800 grit surface pre-heat treatment. I mixed my top-secret special Hamon creating Japanese ancient clay (my grand grandfathers preserved the secret mixture for generations) with water and brought my signature pattern on the blade and let it dry overnight.

The blade – ground to a thin hollow grind – plus the clay for selective hardening led to a serious issue after I dunked the glowing steel into the oil. The steel hardened nicely but I had a really serious warp in the blade – or to better describe it: The edge was wobbly like corrugated sheet metal. No way I could straighten that – only option: reshape the blade. Fortunately the blade was wide enough, even a bit wider than initially designed. And after some more hours of hand-sanding i had a blade that looked better than before.

I also needed to work on the guard piece – also a first-timer: I needed to hot form some steel. I needed more bend than I could archive by just taking away material. And I needed a suiting tailpiece for the handle too, that resembles the form of the front guard.

The blade went up the grit scale from 80, 120, 180 up to 1200 and then on the polishing wheel as I wanted blade, guard, and tailpiece at a perfect nice mirror finish.

I wanted to try something special and etch ornaments or something with meaning into it for the front guard. I went for the Latin words: “Memento Moris – Mors Certa Hora Incerta”. Translated that means “Remember that you are mortal – Death is certain, the time is uncertain”. First I thought about some more etching on the blade but I do not want to overdo the whole piece – especially after I already put so many hours into this knife. But these words are perfect for a knife.

So finally it was time to glue all up and move on the handle shaping. The tailpiece would be the last and glued on in a separate step. Handle shaping went pretty smooth but then I discovered one of the hardest challenges. The tang sticks out from the bottom of the handle And I need to get all the surface around it perfectly flat. That alone took some hours of scratching tiny parts of wood off, just with the tip of the file. I will need to come up with a better idea if I do this kind of handle again – Probably, that I can take the handle off until final assembly.

The last step was to weld the tailpiece to the tiny tip of the tang that stuck out. I am not a welder, I am far from good. So I managed to weld the two pieces but did not manage to get it perfectly and so that it is invisible after grinding, sanding, and polishing the bottom part. You can now see where the two pieces are put together. I am still thinking about trying to weld over it to close the spots – but I am hesitant as it might ruin the knife.

Customer review for the Tigershark by JAMZT53

Joe Topiah

Knife Collector

Instagram <a href=”https://instagram.com/jamzt53/”>@JAMZT53</a>

I’m so Unbelievably excited, impressed, relieved, as my Tigershark arrived today from Germany.. Andreas from @simplyknives, Perfected another Amazing knife for me.. We were very worried that it took so long to get here, but it was worth the wait.. I can’t say enough about Andreas and his work.. (2) words come to mind, “Simply Perfection”

Definition of Meticulous, Andreas Berhinger….

– full tang

– Serpent Wood Handle

– 9” OAL 4.5” blade

– brass pins and lanyard

– hand polished

– Premium (2) tone leather sheath

Thank you so very much my friend.. Your work is second to none.. 🤝🙏🏻

Joe Topiah @JAMZT53

Folder: Spring Folder

My first folding knife model. The spring arrested folding mechanism works like on Swiss Army Knives. The blade is held in the opened or respectively closed position by a strong steel spring that blends into the spine of the handle. The whole mechanism lives inside a strong steel frame. There are no screws, everything is glued up with epoxy. The liners are laminated grey paper and a layer of pearwood veneer to give it a lighter two-color tone. in the closed position, the edge of the blade does not touch any inner parts of the knife to keep it sharp. The handle scales are made out of a nice red Padouk wood.

My blogpost about making this knife

Continue reading “Folder: Spring Folder”My first folding knife

I am working on my first folding knife model. And to make the challenge complete I am trying to build a spring folder where a spring holds the blade in the opened or closed position (like the swiss army knives are made).

The most complicated part is, that all pieces have to fit together very precisely. The spring should not be too strong nor so weak, that the blade is able to wiggle around. This would also be a safety issue. Nobody wants to have a super sharp knife that could open while in the pocket. If the spring is too strong the risk is to slip when you try to close the knife and too much force is needed.

The axis and the connection points have to be set up very precisely. I feel like a clockmaker with fine files and sandpaper, tidying the friction parts up and even polishing them, so they do not scratch in the movement.

I had to experiment with the spring part. It is spacer and spring in one piece and I built it in a way, that the edge of the blade does not touch any internal parts of the handle when closed, so it remains sharp and smooth.

I had to experiment with the heat treatment for springs. I did not find good information on how to do this correctly. The first one was still too brittle and I snapped it and had to build a new one from scratch. When the steel is too soft it just bends and stays in that position. The spring loses all strength after opening and closing the knife after three or four times. In the end, I had a good resistance in the spring and it returns back to position every time.

The liner is a mixed material self-made Micarta. It consists of laminated gray paper and a layer of pear veneer. As all layers are drenched in laminating epoxy it is a waterproof and very stable material mix with a nice optical effect.

For the handle, I chose Padouk wood, a very nice and easy to work with material. It has good material properties and a coarse porous texture – The only thing was that it covered my whole workshop with a red layer of dust.

The etching says “spring folder” but the font I chose did not come out as expected, so next time I will choose a better-to-read font.

Another first-time was the use of my new polishing machine. That thing is kind of scary with the high speed and power. But it gets the polishing job done very nicely and it is so much more convenient instead of using a polishing wheel on my drill stand.

I am very happy with the results of my first ever made folding knife. I learned a lot – like always – and I can improve on that experiences for the next models.

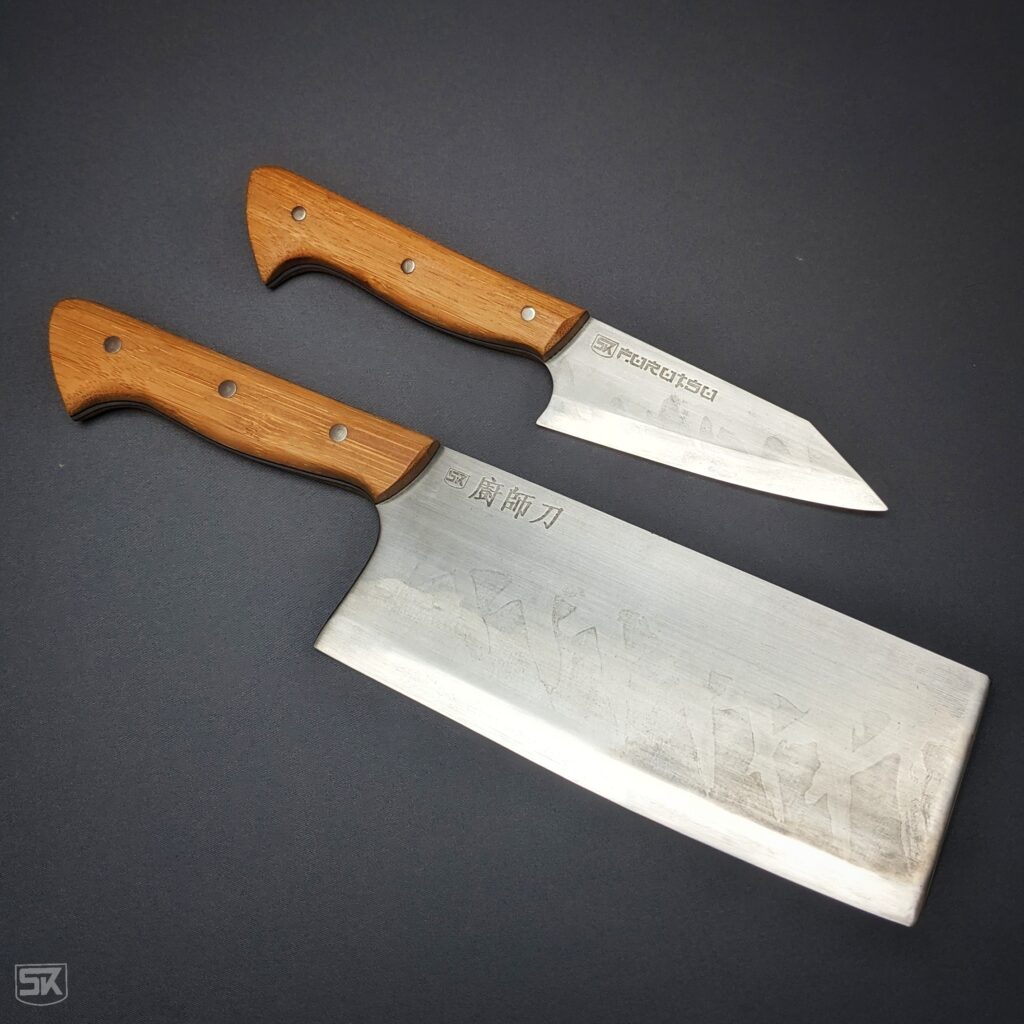

How I made two Asian style kitchen knives with a Hamon

I have recently finished more kitchen knives. I worked on another Japan-style Furutsu petty knife and a Chinese chef’s knife.

I used 2 mm O1 steel for these knives as this gives a good mix of stability, flexibility and thin enough to be highly sharpened. O1 is my favorite steel to work with.

On my last order of handle material, I changed the supplier and checked out some of his materials. I found that he offered bamboo handle scales and as I already planned to do Asian-style knives I found them to fit perfectly and got two sets. The bamboo is not a solid block but more layered or stacked. I still like it a lot.

My first tries to add a Hamon

I always try to learn something new – this time I wanted to experiment with creating selective hardness in the blades and a Hamon. A Hamon is a wavy line between the hardened part of the blade – the cutting edge – and the spine of the blade, where the steel stays softer. The advantage is, that the hardened blade is supported by a softer part of the blade which results in a more stable knife – and to be honest: it looks just super cool.

To create the Hamon I prepared the blades as usual and then I created a mix of ash and clay. The recipe for the exact mixtures is a secret that is passed from generation to generation in our family. The clay is left to dry. Then the blade is heated together with the clay mantle and hardened in the oil.

After hardening the clay is removed and the blade is tempered and then hand sanded to the desired grit and then etched in ferric chloride, then sanded again. I repeated the etching and sanding process multiple times to reach the desired look.

For my first try I am very happy with the result. Must be due to the secret clay recipe of our family 🙂